Book Review: TechGnosis

Myth, Magic and Mysticism in the Age of Information... and some other weird stuff

There’s always two questions I ask myself whenever I start a new book from The Reversion Book Club book list and that’s:

Why does Anthony want me to read this?

Why does the author of the book want me to read this?

In either case, for TechGnosis, I’m not entirely sure of the answer. I thought I joined the Reversion Book Club to read some wholesome, likely ancient, Christian works but instead I’ve found myself in forbidden section of the library.

To be fair, Anthony did throw in The Making of Holy Russia, but that book was so dense with historical fact it almost crippled me (no, I haven’t finished it but God Willing, I will).

That’s not to say you shouldn’t read TechGnosis or join the book club, but if you are a baby Christian like me, your time might be better spent reading more practical texts.

What am I saying, perhaps only to myself, and very very if I may, is that if you are a Baby Christian, like me, you should work to get a better understanding of your actual Christian faith rather than reading esoteric stuff on Gnosticism. However, if you are into the esoteric, then this book is probably right up your alley.

I only vaguely knew what Gnosticism was before reading this book, come to find out it is the original heresy of the Church. Indeed, the more I read through TechGnosis, the more I kept thinking to myself, “based on what I know, this book seems like it’s documenting the rise of the AntiChrist, or, at the very least, the rise of everything anti-Christian.”

While I would say Davis isn’t overtly against Christianity, he does seem to present it in a negative light throughout the book. And perhaps, that is why Anthony wanted us to read it: the echoes of Gnosticism can be seen throughout contemporary society today (especially in “technology”). America being absolutely full of it:

America’s political embrace of the modern individual was also motivated by the land’s curious spiritual temperament - a temperament that, in its quest to discover a motive ground outside of governments and established religious institutions, appears to be the very antithesis of religion as we know it.

The author, Erik Davis, doesn’t make any obvious conclusions. And he writes in such a way that if you aren’t paying attention you’ll probably miss the point. He merely presents information, through varied prose and analogies, to the reader. Like this:

Maxwell showed that light - the ultimate symbolic manifestation of divinity - was itself only a certain range of frequencies that happened to stimulate the two photosensitive orbs lodged inside the human skull.

Eyes. He’s talking about eyes… Over and over, you’ll find yourself stopping and saying, wait… what did he say?

Davis doesn’t even seem for or against Gnosticism, or tech-gnosis or whatever. He’s just collecting and presenting facts. And most of those facts are humans doing some weird and sketchy things via technology, specifically information technology. Ironically, there’s no chapter on the IT guys who are just average nerds sitting in a windowless room of a corporate office swapping out hard drives for a living which is probably the main demographic for this book.

What Is The Meaning Of This?

For a long time, I kept asking myself, “What point is this guy making? Why am I reading this? Why?!” It wasn’t until Pg. 78 that I feel like he broke the fourth wall:

Gnosis forms one of the principal threads in the strange and magnificent tapestry of Western esotericism, and I must emphasize that my use of its lore is not intended to belittle its possibly illuminating powers. Hermetic scholars or occult traditionalists would write off any similarities between Gnostic religion and contemporary technoculture as, at best, the latter’s demonic and infantile parody of the former. But the authenticity of spiritual ideas and religious experiences does not really concern me here; rather, I am attempting to understand the often unconscious metaphysics of information culture by looking at it through the archetypal lens of religious and esoteric myth. Inauthentic or not, these patterns of thought and experience have played and continue to play a role in how humans relate to technology, and especially the technologies of information.

Gnosis is the Greek noun for knowledge. Gnostics said that the knowledge given to Adam and Even in the Garden of Eden was “good,” that this hidden knowledge could liberate them from their evil Demiurge’s control, and that human beings use this gnosis to sort of evolve passed the faulty design of the universe.

TechGnosis is basically all that except that we use technology to transcend too. And this book tracks the weird ways humans have used technology to transcend throughout the ages.

To get a quick taste of hermetic America, simply take a dollar bill, flip it over, and try to stare down the glowing eye that tops the pyramid of the great seal. Like the Byzantine icons of Eastern Orthodoxy, which can catalyze a flash of beatitude in the eys of their viewers, so can this decidedly weird symbol of the novus ordo seclorum (a New Order of things) conjure up the secret architecture of power tucked beneath the bright and shiny pragmatism of the United States’ federal government. And this architecture’s name is Freemasonry.

While some of the stuff in the book is certainly interesting and worth paying attention to, other stuff just seems a bit out there. Like Davis just threw it in because it was even remotely related to technology or transcendence.

On the one hand, you’ll enjoy learning about America’s “esoteric undercurrent” revealing itself in the form of Freemasonry, on the other hand you’ll waste a few hours of your life learning about ‘technopagans.’ For example, and yes, it is taken out of context, of course, but tell me, dear Friend, tell me, Payload, does this quote have anything in it that sounds interesting to you?

By the 1980s, hundreds of electronic Pagan BBses dotted the land, boasting names like El Segundo Spiders Web, the Fort Lauderdale Summerland, and Ritual Magick Online. The anarchic environs of the Internet, with its chat lines and newsgroups, swelled with Wiccans and druids, and Usenet’s alt.pagan and alt.magic hierarchies became flaming cauldrons of debate.

Reading this chapter, and other chapters like it, I couldn’t help but think, release me from this Hell. To me the book YoYo’s like that the entire read: something interesting one page, then something bizarre the next. Maybe that was the point. Regardless, I was determined to finish this book (as well as all the others from the Reversion Book Club book list) and so I stuck it out to the end.

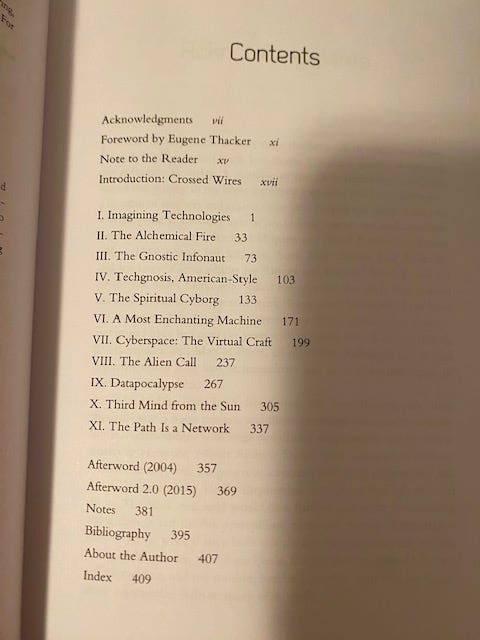

The Table of Contents

Here’s the contents:

Before you rip away through the pages of TechGnosis, I implore you to define any of the terms you don’t immediately recognize. For example:

alchemical: involving a seemingly magical process of transformation, creation, or combination "writing a novel is an alchemical task"

gnostic: relating to knowledge, especially esoteric mystical knowledge

information: facts provided or learned about something or someone; what is conveyed or represented by a particular arrangement or sequence of things.

You might “think” you know what is meant by information by Davis usually uses the (ironically) esoteric meaning of the word. If you don’t define terms, you’ll quickly lose yourself in a sea of nonsense.

But once you start reading, buckle up, because it is a bit weird to slowly learn that everything you know or love, or knew and loved, had origins in the occult.

Heron was not just some cynical Oz popping up decadent priests; he was designing popular spectacles designed to catalyze ecstasy and wonder, classic analogs of EDM festivals or theme parks of our time.

Far from leading to brain-rotting superstition, the magical animism of alchemy and other hermetic arts helped spur those practices and paradigms now known as science… the origin of modern medical Pharmacology, Paracelsus’s researches were embedded within a deeply magical worldview awash with spiritual agencies and millennialist dreams of human perfection… from optics to astronomy to chemistry, many of these findings first crystallized in an occult crucible.

The reader must keep in mind that the original published date for TechGnosis was 1998. For those of you who are young, you don’t understand how much has changed since 1998. We used to have to dial up to get internet connection. You literally had to press a button on your computer and watch it attempt to connect. It might as well have been a different world. My point is that most of the stuff you read in this book is for the only hardcorest of nerds. (See that quote above).

But the other point is that back then, the internet truly was “mystical” or, at the very least, “a new frontier.” It wasn’t the smoothed over, consumeristic, easy-to-use-thing that you see today. It was a barely regulated mess of computers that were all connected by ethernet cables.

Today, code is handed out to everyone willing to pay. That’s why everybody’s website looks identical. But back then, you had to code your own sites and so every site you went to felt like a new location. And since no one knew anything, hacking was far easier back then, too. Click on a sketchy link and you might be traumatized for life.

I don’t remember every trying to “transcend,” via the internet but that doesn’t mean it wasn’t happening. TechGnosis shows you that it certainly was happening. But the people willing to transcend over the internet back in the day had to be the most esoteric of folk. Davis calls them something else: Technopagans, Wiccans, lol. They had to go on the internet because no one wanted them around in real life. A lot of the stuff he mentions in the book died out long ago. If something barely has a Wikipedia page, it’s probably a good sign that it never amounted to much:

Either that, or it simply took on a new name… “science and technology will some day let people live indefinitely.” Does that sound familiar?

The Extropians have spent a lot of time plotting out neo-Darwinian future scenarios dominated by AI, nanotechnology, smart drugs, weird physics and massive government deregulation.

Like I said, while some stuff seemed like it actually was “TechGnosis,” I couldn’t understand why Davis would throw in entire chapters on some of the most random stuff, like Phillip K. Dick, who was just a novelist imagining crazy things from something that appears to be drug induced psychosis. Or the entire chapter on Adventure, some garbage video game from the 80s. I don’t know.

Conclusion

I give respect to Davis because I know good writing when I see it. The man does have the ability to crafty a wily sentence which is something you don’t see much of these days. The fact that he name drops both Thomas Pynchon and James Joyce tells me the man is either a “fine” literature connoisseur… even though Gravity’s Rainbow and Finnegan’s Wake were damn near unreadable… or he is simply that, a name dropper. The writing in and of itself was my favorite part of the book with the content being secondary.

But still, putting all that content together seems a like a daunting task that deserves credit. I don’t yet know how some people like Anthony, or Payload, or Davis here have the ability to collect massive amounts of information to craft an article or a book but perhaps overtime I will.

For now, I will simply respect such men who add to the Age of Information even if half the time, I don’t know what they are saying. Regardless, I don’t think any of the weird, esoteric knowledge you get from reading TechGnosis will help you transcend, let alone save your soul.

I have written way too much already and covered way too little. From Hermes to the UFO Deception, the book covers such a wide spectrum of topics, its’ impossible to explain. In my estimation, you can’t really read this book fast, nor can you just read it one time. If you are like me, you’ll want to read it fast just so that you can move on with your life.

My notes got out of control. Half the book was underlined and I had multiple index cards full of random jargon:

I told Anthony this book was above my Pay Grade and I meant it. Should you decide to read it, get ready for long chapters, little font and teeth chattering amounts of coffee.

Related to your article, that’s why I did McGowan’s “Programed to Kill” in the Book Club. Initially you say what’s the point of reading something like this but once you actually process the book you don’t see the world the same way.